Chapter One: The Embers

They’re calling it burnout.

I think it's too familiar a term for something so scary and unknown. Before, burnout was associated with words like stress, vacation, or drug use. On the last day of our summer retreat at The Circle, with my son standing just to my right, we hear it used with much different words. Suicides. Bodies. Children.

I typically have a difficult time focusing on the Mother’s words at the last meeting of our retreat, anticipating our travel home. Today I am watching them leave her mouth like slow motion smoke rings one letter at a time, expanding until they dissipate in the heavy stillness of this cabin.

Four hundred and twenty-seven suicides by children under the age of twelve in the past month and a half.

I am standing beside my child in a wooden house in the woods in the middle of nowhere. Suddenly it feels like we are locked in a time capsule. I’m having trouble breathing. We are listening to a one hundred and seventeen-year old woman wrapped in white read the most horrifying information imaginable. I grab his hand and squeeze it tight. I haven’t looked at his face but I can feel him. He is confused. He’s scared. He’s more scared of my shaking than of the words the Mother is saying.

…media has stopped using the word suicide...they’re calling it burnout.

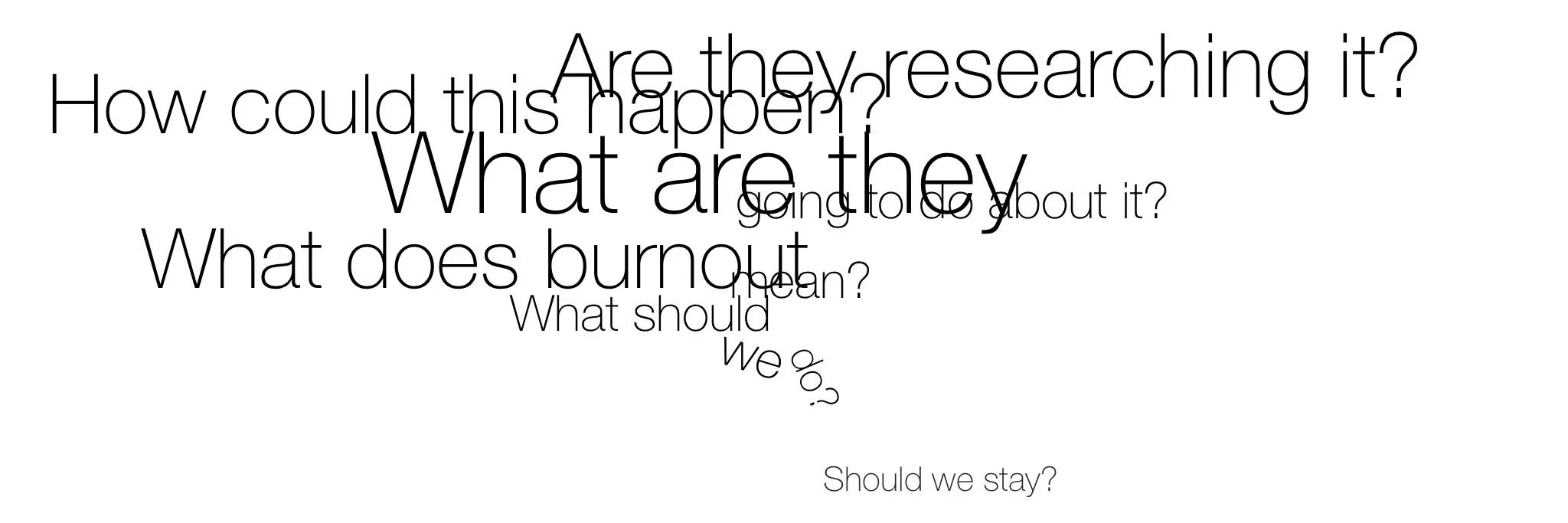

Sweat is rolling down my forehead. My mind is running around holding the Mother’s words like a lit firecracker, frantically looking for a window to throw it out of before it explodes. The group is talking now, responding as you would imagine.

When I open my eyes, I see my blurry son staring at me, inches from my face. My eyes struggle to focus on his. His tears are falling onto my cheeks, rolling down into my ears. When his eyes come into focus, I smile at him, an involuntary reaction I have had to these crystal blue kaleidoscopes since he was born. He hugs me tightly around my neck, sobbing a whisper in my ear.

“I thought you died this time”.

I manage to get off the floor and into my car with his face buried into my neck the entire way. My shirt is soaked with tears and I can feel his embarrassment. I don’t remember the last time I carried him like this. His skinny limbs are dangling around me like a spider and he has completely given himself over to sobbing. I sit him in the car beside me, waiting for him to calm down.

Be still. Breathe.

I used to worry that coming here for an entire summer completely off the grid was irresponsible. What if something bad happened? I decided that this thought was flawed in every way, so here we are, for the fourth summer in a row. The reality of the something bad that is happening is far worse than any my anxious imagination ever invented. My mind is whipping out of control.

Be still. Breathe.

I whisper it over and over, rhythmically running my hands through his hair until his sobs subside. I drive away from the Circle as he falls asleep in the seat beside me, the occasional soft burst of sighs rippling through the silence like an aftershock.

Once I’m sure he is asleep, I turn on the radio so low I can barely make out the words. The burnouts are being speculated about in the broadest possible terms, but autopsies are pointing to issues with sensory processing. Interviews with children’s families do not yet show commonalities or disorders, so the next focus is changes in environmental radiation and possible electro-sensitivity. The reporter is jumping between conversations with experts in child psychology and radiation. They are now talking over each other, listing games, devices, and random technology recently released, their words braiding together until they are incoherent. We are past the point of shielding our children from the awful things in our world that you can see and describe. We’ve moved on to trying to shield them from the invisible.

I turn the radio off. Most people I know have a ticker, and never have to wait for anything to know what’s happening. Long blink on. Two taps of the left thumb and forefinger off. One tap pause. The tickers are customizable in every way from the body language that controls them to their delivery method. You can hear information only, see it and hear it, watch images with captions, scan and alert only on certain topics. You can even set them to turn on and off by tracing a pattern onto the roof of your mouth with your tongue. Some people think this is the beginning of the end of our humanity; I am equally fascinated and terrified by it. I used to like walking through crowds of people, looking for their ticks. Some people are theatrical about it, waving their arms and using verbal cues, and some are self conscious and try to hide them completely. I had my ticker removed when I discovered that I could turn it on and off with my thoughts. At the time there was no setting for that.

I notice goosebumps on my son’s bare legs and reach over to cover him with my wrap. He is sleeping with a furrowed brow, moving occasionally like he does when he has a bad dream. My mind begins the familiar backstory of what I know will quickly become panic.

He’s always been so sensitive. His heart is fragile. Could he become sensitive to radiation from being away from it completely in The Circle all summer?

When I first realized that my son and I could communicate without words, learning how to interrupt the cycle of thoughts like these suddenly became much more important. As if on cue, I feel him tap my arm. I take a deep breath, loosening my grip on the steering wheel and lowering my shoulders as I exhale.

I try to keep my voice from shaking when I ask him what’s up. He pulls my wrap over him and tucks it under his chin before he speaks...